Met regelmaat lees ik de nieuwsbrief van The Met. The Met is

een belangrijk museum in New York met regelmatig aandacht voor Azië.

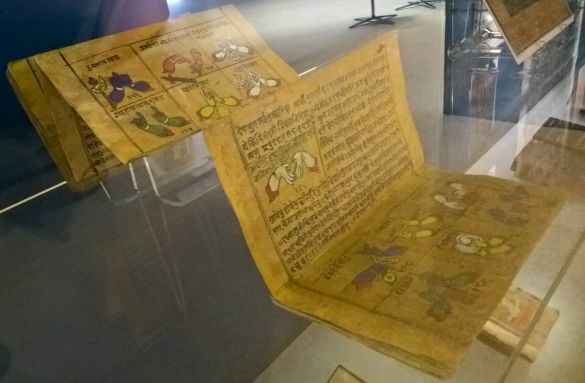

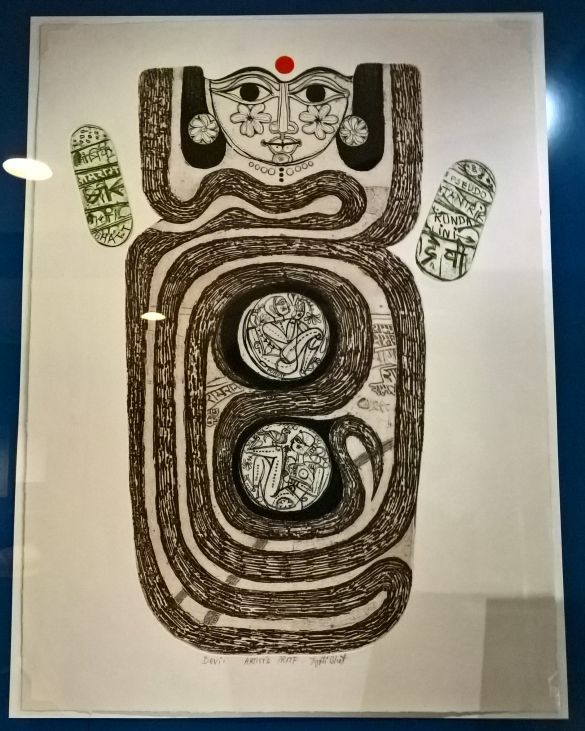

Op dit moment loopt daar de tentoonstelling ‘Tree & serpent’.

Het gaat over vroege Buddhistische kunst.

Grappig dat in het Boeddhisme de boom en de slang een heel

positieve symboliek heeft als de vertegenwoordigers in

kunstuitingen van de Buddh die er in persoon niet te zien is,

terwijl in de Christelijke symboliek deze twee elementen ook

voorkomn. Al was het maar in het verhaal van de Zondeval waarin

de slang, vanuit een boom, Eva overhaalt om van de appel

te eten.

De teksten zijn van de tentoonstelling.

De tentoonstelling gaat uit van de functie en vorm van de stupa.

In de video wordt daar ook op ingegaan.

De museum website doet wat krampachtig over de ‘rechten’ van de afbeeldingen. Ik zou ook graag de voorwerpen in eigen persoon bekijken maar dat zou een wel erg duur avontuur worden. Maar er zijn toch drie voorwerpen te zien in dit bericht. In de film die gemaakt is en die op internet te vinden is, kun je deze en nog meer voorwerpen ook bekijken.

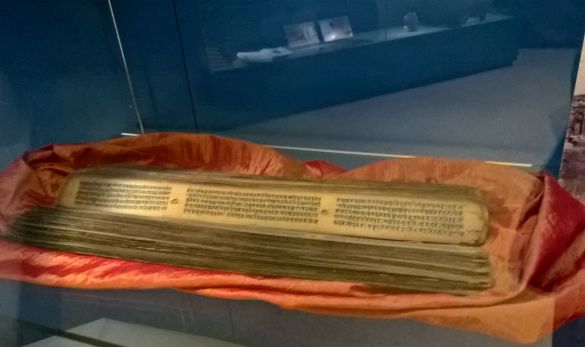

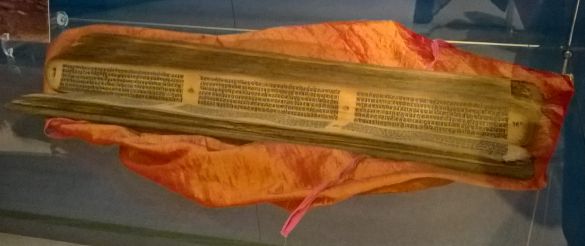

This is the story of the origins of Buddhist art. The religious landscape of ancient India was transformed by the teachings of the Buddha, which in turn inspired art devoted to expressing his message. Sublime imagery adorned the most ancient monumental religious structures in ancient India, known as stupas. The stupa not only housed the relics of the Buddha but also honored him through symbolic representations and visual storytelling. Original relics and reliquaries are at the heart of this exhibition, which culminates with the Buddha image itself.

Featuring more than 125 objects dating from 200 BCE to 400 CE, the exhibition presents a series of evocative and interlocking themes to reveal both the pre-Buddhist origins of figurative sculpture in India and the early narrative traditions that were central to this formative moment in early Indian art. With major loans from a dozen lenders across India, as well as from the United Kingdom, Europe, and the United States, it transports visitors into the world of early Buddhist imagery that gave expression to this new religion as it grew from a core set of ethical teachings into one of the world’s great religions. Objects associated with Indo-Roman exchange reveal India’s place in early global trade. The exhibition showcases objects in various media, including limestone sculptures, gold, silver, bronze, rock crystal, and ivory. Highlights include spectacular sculptures from southern India—newly discovered and never before publicly exhibited masterpieces—that add to the world canon of early Buddhist art.

Railing pillar with naga Mucalinda protecting the Buddha. Pauni, Bhandara district, Maharashtra, Satavahana, 2nd–1st century bce, sandstone. Inscribed: Naga Mucarido [Mucalinda] and a female donor mahayasa. National Museum, New Delhi.

This enclosure railing pillar, from a monumental stupa some 135 feet in diameter, dates to the very beginning of the Buddhist figurative sculptural tradition in the Deccan. Its decoration is an inventory of early Buddhist imagery—the lotus, snake, tree, empty throne, and worshippers—and bears stylistic links to the early rock-cut caves of the Western Ghats mountain range. The monastery to which it belongs was likely founded in the third century bce, at the site of the ancient kingdom of Vidarbha (modern Nagpur). Its capital, Kundina, is described in the Sanskrit epic Mahabharata as a great and beautiful city, and is also referred to by the Greek scholar Ptolemy in Geography (mid-second century ce).

Stupa drum panel with protective serpent. Amaravati Great Stupa, Guntur district, Andhra Pradesh, Sada, second half of 1st century ce. Limestone. British Museum, London.

This drum panel depicts an elegant stupa with a shrine, at center, framed by pilasters that resemble a stupa enclosure railing gateway. The entwined snake that occupies the shrine is the naga, the supreme protector of the relics housed within the stupa drum. A canopy of foliage-like umbrellas (chattras) crowns the structure, with the branches of the bodhi (wisdom) tree metamorphizing into a profusion of honorific umbrellas. Inscribed railings from the period link the donors to officials in the service of King Sivamaka Sada, the last of the Sada rulers, reigning in the second half of the first century ce.

Dome panel depicting a royal worshiper Amaravati Great Stupa, Guntur district, Andhra Pradesh, Satavahana, 2nd half of the 1st century ce. Limestone. Inscribed in Prakrit, Brahmi script: Made by [?] son of Dhamadeva, the Virapuraka [resident of Virapura], the gift of [?] female pupil of Budharakhata. British Museum, London.

This panel from Amaravati is among the oldest portrait sculptures preserved from the Andhra territories. It depicts a Satavahana king with his hands in veneration. He is attended by a queen, a general (leaning on a war club), and women holding fly whisks and an umbrella. Although he lacks the other attributes of a Buddhist universal monarch—

notably the elephant, horse, Dharma-wheel, and jewel—his royal status as a king at worship is clear. An empty throne in the fragmentary upper register references the Buddha’s presence. The donor inscription records the gift as from a wealthy woman who took spiritual instruction from the monk Budharakhata.

Ik heb de catalogus gekocht.

De voorwerpen van het British Museum zag ik er in 2018

en daar schreef ik toen over.

Ook in mjn bericht uit 2021 over een bezoek aan het National Museum

in New Delhi zie je voorwerpen van de tentoonstelling terug.